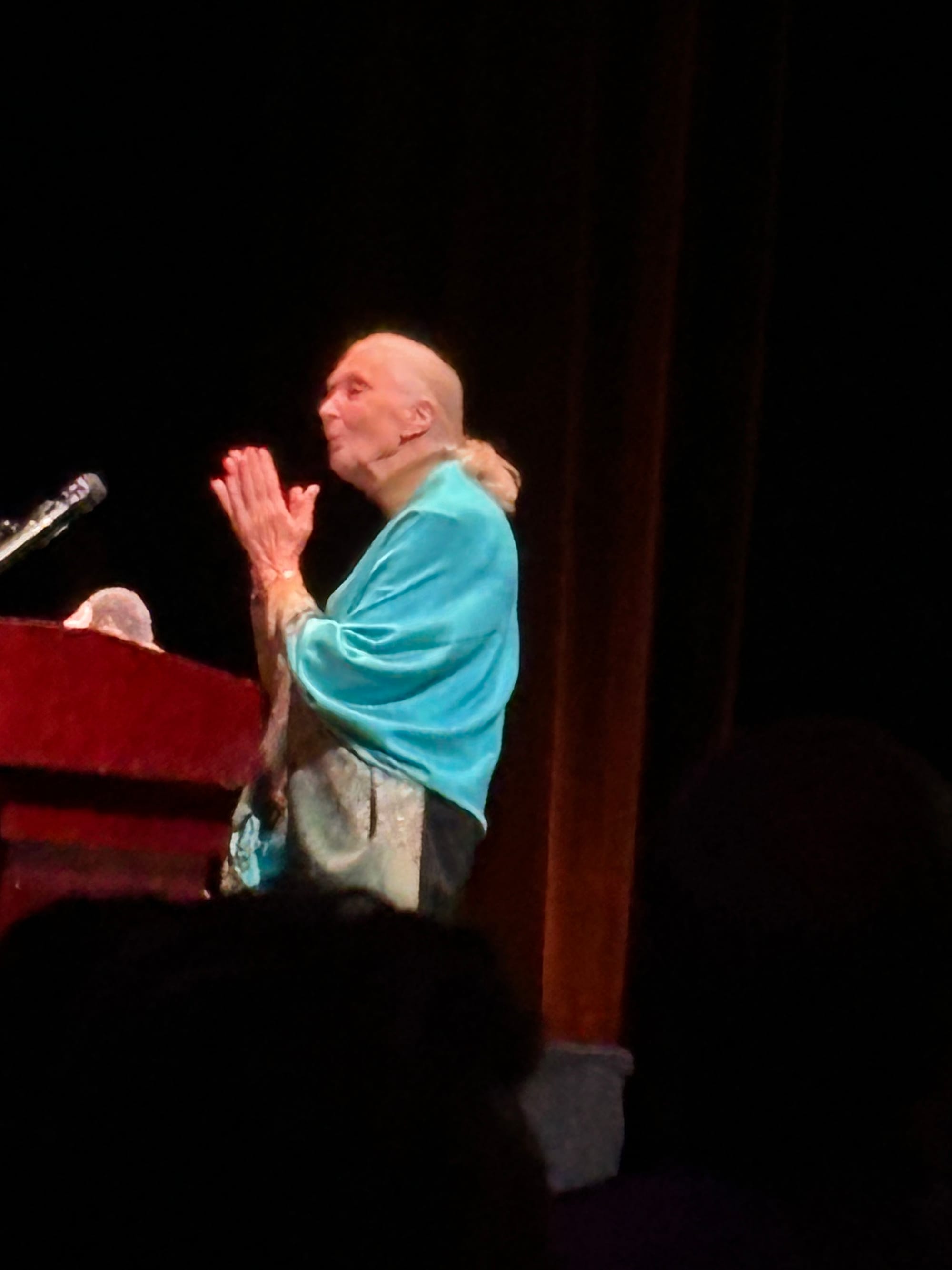

An Evening with Dr. Jane Goodall

When I am ninety years old, I want to look back on my life with the same amount of grace, wisdom, and humor as Dr. Jane Goodall does. The famed primatologist spoke in Atlanta this past Wednesday night, not only about her pioneering work with chimpanzees in East Africa, but of the singular role her mother played in nurturing her love of and curiosity about animals.

Some mothers might have lost their cool if they found their kid in bed with a fistful of earthworms. Vanne Goodall was not one of those mothers. She saw her child’s wide-eyed wonderment about how these creatures moved without legs and chose to view what was happening as “Jane’s first animal research program.” From earthworms, Jane moved on to chickens, and once spent four hours in a henhouse to see a chicken lay an egg. She read everything she could about animals and romanticized about living among them, just like Tarzan did. Family finances complicated her pursuit of a college degree, but Goodall was determined, and her mother never dissuaded her from giving up on her dream. First, she was realistic with her daughter, and said the road would be hard. But she said if Jane worked hard and took advantage of every opportunity that came her way, things would work out.

Her mother was right (ed. note: listen to your mom, always and forever). After working for a few years as a waitress and secretary, Jane was invited to visit a friend at her family farm in Kenya. Soon after her arrival, she met the famed paleoanthropologist Dr. Louis Leakey, who was impressed with her insatiable desire to better understand animals. Though Leakey originally hired her as a secretary, in time he believed that she was the right person to do field work on chimpanzees as a way of understanding humankind’s evolutionary past. He liked that she had a mind that wasn't cluttered with the restrictive ways researchers viewed animals at the time.

Local authorities did not want a young woman doing this work all by herself. So, Jane’s mother decided to join her on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, and provided her with the moral support she needed as she slowly, steadily gained the chimpanzees’ trust. After months of intense study, she determined that humans were not the only ones making and using tools. Chimpanzees were doing it too, and her observation was a game-changer in animal behavior research. More discoveries followed, and Leakey arranged for her to get her PhD at Cambridge. One wonders what her path might have been without a mother who saw what made her child light up and encouraged her along the way.

For decades, Jane Goodall’s work has shown us that we are all connected. The choices we do – or don’t – make, the things we say, the items we purchase, the food we eat, the way we behave (or misbehave) all of it impacts someone or something somewhere else on the globe. If we know this, then perhaps, as she suggests, we should approach our decisions in a way where heart and head are more aligned. That’s the sweet spot for unleashing the best in human potential. She knows mankind is capable of great things – like creating robots and sending rockets to Mars. She knows we are capable of solutions. And she is heartened by the youth who are standing up to make a difference in their communities. She chooses to focus on that and offer solutions for things that seem too hard and horrible to contemplate. I was grateful to hear this icon speak on Wednesday night, and deeply inspired by what she had to say.

The first thing I did after I left? I called my mother and thanked her for encouraging me to become who I’ve become, and for giving us her all, even after a long, hard day. This weekend, I hope you’ll call your mother too, or at least think fondly of a time when she gave you what you needed most, even though you may not have realized it (or appreciated it) at the time.

Writing prompt: When you think of your mom, what comes to mind? Go with this where you will and see what unfolds on the page. If you could thank her for anything, what would it be and why?

Please, take my euros

I'm not sure how and why I missed this, but over the summer 32-year-old Austrian heiress Marlene Engelhorn recruited fifty fellow countrymen from all walks of life and asked them for help giving away $27 million of her inheritance. Engelhorn, who grew up in a posh part of Vienna, was conflicted about growing up with wealth she did not earn, and that the state did not tax. Because the state was not doing enough to redistribute wealth to people who needed it most, she decided she would take matters into her own hands. She would give away ninety percent of her inheritance, even if it meant she would eventually have to get a job. After selecting the fifty people who would serve on her council for redistribution, the heiress had some rules for where this money could go. According to The New York Times, they were:

The money could not be given to groups or people who are “unconstitutional, hostile or inhumane,” and it could not be invested with for-profit institutions. The money also couldn’t be redistributed to group members or “related parties.”

“When you grow up wealthy, it’s not that one day you realize how much money you have,” Engelhorn said. “But, rather, that there is such a thing as people who don’t.”

For more on Engelhorn and this experiment, check out this fascinating feature in the September 2, 2024 issue of The New Yorker.

Endnotes

What I'm reading: Carrie Rickey's new biography "A Complicated Passion" about filmmaker Agnes Varda. Sebastian Smee's "Paris in Ruins: Love, War and the Birth of Impressionism."

What I'm listening to: Anything Sade sings. For some reason, this moment seems to require something smooth and soulful. Also, that Naomi Campbell mix from last week's newsletter is pretty great.

What I'm looking forward to: Today's trip to the High Museum to see "Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys."

Where I hope you'll donate this week: In 1900, an estimated one million chimpanzees lived in the wild. Now, there's about 340,000, and thinking about that just makes me sad. The Jane Goodall Institute is working to save the chimps and the natural world we all share, but they can't do it without our help. If you can, please consider a donation so they can continue to make a difference globally.

Paige Bowers Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.