Dancing Flamenco with Julie Galle Baggenstoss

"We are not strippers. We do not dance to mariachi or salsa music."

Another week, and another treat for you, fair readers. This week's interview is with Julie Galle Baggenstoss, a flamenco performer, choreographer, teacher, and impresario. She is also, I'll admit, one of my oldest, dearest friends, and a force to be reckoned with.

A little more about her: Julie is known across the country for her work on stage and in educational projects involving Spanish artists. Close to her home of Atlanta, she has performed and choreographed flamenco with the Atlanta Opera, Georgia State University's School of Music, The Latin American Association, Coves Darden P.R.E., and at universities and museums from the Southeast to the Midwest.

Julie teaches flamenco in the Dance and Movement Studies Program at Emory University. She is a former instructor of the Atlanta Ballet, and is a teaching artist for organizations such as Woodruff Arts Center, the Rialto Center for the Arts, the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese, the Foreign Language Association of Georgia, and Georgia Public Libraries. In 2019, she launched the Atlanta Flamenco Festival, which will be taking place August 26-31 this year, so you should definitely go check it out! Read on for more about this former journalist's journey toward the art form, and how she's sharing it with a whole host of audiences far and wide.

Q: When did you become interested in flamenco and why?

A: I took my first flamenco class in the 1990s in New Orleans. I had danced for twenty years before that, with tap being my forte, and I was ready for another kind of percussive dance. I tried to take an Irish dance step class (think Riverdance, not Rose and Jack on the Titanic), but the teacher looked down his nose and told me, “We only teach that to children.” In the devastating silence that followed, I heard the pounding of footwork on the other side of the wall. I found flamenco dance there.

Q: When did you realize your interest in flamenco was going to become more than simply taking a class here or there?

A: When I was in New Orleans, my mysterious teacher, Teresa Romero Torkanowsky, gave demonstrations of flamenco dance at schools and to community groups. When I moved to Atlanta, I realized that no one was really doing that in the city, so I decided to give it a try. I leaned on what I learned from Teresa, who also was a contemporary of the legendary Carmen Amaya. They worked together in North America. Teresa herself was a big deal. Her reluctance to speak about her heyday as a renowned performer and impresario inspired me to investigate what she did in flamenco. That was just the beginning of my understanding of flamenco in the U.S.A. and Spain.

Q: At what point did you realize you needed to go to Spain to learn from performers there? What was that experience like for you? And how often do you return to Spain to connect with the community there?

A: I moved to Atlanta and started taking classes with local teachers. One of them told me that I needed to go to Spain to learn. I looked around the U.S.A. first, not sure of the need to spend the money and effort traveling internationally. Keep in mind, this was the early aughts, when we planned travel by reading that small print in Lonely Planet to find hotels or hostels that hopefully were still in existence, and, once abroad, we used calling cards at pay phones to make contact with locals or our loved ones back at home. The artists, teachers, and studios, listed their classes on paper fliers posted around the small towns where they lived, and even then, they were difficult to actually locate. I opted to travel to Spain when I realized that being in those small towns and experiencing the atmosphere first-hand would be part of my flamenco education. It was first-hand research, and it is something that I talk about all the time in lectures. I have returned to Spain nearly every year since that first trip in 2003, sometimes more than once in a year. I visit libraries, speak with artists and historians, attend performances, and socialize, too. I have cooked with my friends and brought their recipes home to my kitchen. I have changed the way I do my laundry, and I am even known to walk Atlanta instead of driving, because experience in Spain has shown me the benefits of getting off the wheels sometimes.

Q: How did you establish yourself in flamenco? Who were your mentors and how did they shape your approach to the dance and bringing it to audiences?

A: I spent a lot of time with musicians. Yes, I have taken thousands of hours of dance classes. But, I learned to sit with the musicians and listen to how they talk about the art form. Understanding their roles changed the way that I use the dance steps that I learn. It also helped me begin to create my own, because our dance exists to amplify the music.

I spent a lot of time teaching everywhere, setting dance for anyone that needed it, and performing every place that I could. Now, it is a little different. But, during those 10 years or so, I hired musicians and dancers who had more experience than me to work with me. I combined what I learned in classes with what I absorbed in rehearsals and performances in a system of continuous improvement. I still do that, and it is an adrenaline rush.

Ah, a list of mentors is long in retrospect. Here are the names of a few more people who took time to give me honest and constructive support over many years. Meira Goldberg, a published author in flamenco history and a very accomplished flamenco dancer, over 20 years has helped me see that you could be smart about flamenco and be a performing artist, if you spend your time wisely and focus on accuracy in details. She has published work about the African influences of flamenco, which informed my M.A. thesis, directed by Elena del Río Parra. All of that has led me to explore ways to connect flamenco with African-American expressions in the South. There is a lot to explore there starting from a shared rhythmic origin.

Cristian Puig, guitarist, singer, and composer, trusted me early in my career to accompany my dance and go on the road to perform with me. He always has honest conversations with me about the intersection of music and dance and the difference between art for art’s sake and performing to charm an audience. His perspective his interesting, because he is from Argentina, his family is from Jerez de la Frontera, Spain, and he worked in New York for decades. Learning about audience perception in the U.S.A. has helped me market flamenco and mold the content of concerts.

Juan Vergillos is a flamenco historian who challenges the popular view of flamenco history with documented evidence and encourages me to always question facts, even the published ones. There are lots of popular trends in flamenco, and he usually debunks them, always bringing me back to the point of origin.

Juan Paredes is a flamenco dancer from Seville, Spain, who I met over 10 years ago, when I was starting to incorporate conceptual rules of flamenco rhythm, such as a relative method of counting, as means to demonstrate new perspectives in creativity in public schools. He has guided me to unlock more of those rhythmic anchors and encouraged me to broaden my capacity as a practitioner of the art form, as well as a producer.

Antonio Granjero is an accomplished flamenco dancer and entrepreneur who comes from a strong school of flamenco dance in his hometown of Jerez de la Frontera, Spain. He has helped me understand professional roles, musicality in dance, and the important details of great dancing. Antonio has built a strong reputation for producing solid concerts with super talented artists from Spain. His work sets a bar that I try to match in the concerts that I produce.

Q: What did it take for you to establish relationships with performers here and in Spain?

A: In the beginning, I just made a bold phone call or bravely sent an email, thinking the worst they could say was no. Through the Rialto Center for the Arts, I presented Mañuel Liñán in Atlanta back in 2013, and that was the result of one such crazy question. I just walked up to him and asked how to book him. He connected me with his manager, who I met in Madrid the following spring (on the day of the first protest of the Occupy Movement, which started there with tents and cardboard box huts in Puerta del Sol). From that coffee meeting, we planed a performance, and that was my initiation into flamenco management. I was as in awe of the manager for her work as much as I was crazy about Liñán for his artistry. I produced my own show within a year of that one, contacting artists directly. For that concert, I remember being on the street corner in Seville one winter afternoon, convincing an artist to accept an invitation. He was a rising star, and another producer and I were ready to hire him – if only he would be brave to travel to perform. He did it! That is an example of a new relationship that I have with artists. It means a lot to sit with them, because so many times the passion that brings them fame on stage comes from their deep love and devotion for flamenco as a means of expressing themselves in everyday life. That sense of being ingrained in the art form is very special, and those are the artists to whom I am drawn more and more. Lots of artists have declined to work with me for one reason or another. I have slowly begun to find ways to increase funding so that we can bring stars to Atlanta. I now bring artists to Atlanta twice a year to perform in series produced by the non-profit A Través. I also bring other artists to work in concerts and classes presented by my production company Berdolé. It is my dream to bring Liñán back one day. He is a really big deal now, so we need lots of funding for that one.

Q: You launched the Atlanta Flamenco Festival in 2019. This year’s festival is August 26-31. First, tell us what it took to get something like this off the ground, and how it has been received. Second, tell us what we can expect from this year’s festival.

A: It took a lot of money to get the festival off the ground. At the non-profit A Través, we actually began the idea in 2016, but didn’t name it until 2019. So, for a few rounds in those years, we brought acts to Atlanta and presented a cluster of classes and concerts in different venues around Atlanta. We wanted to present flamenco as it is in Spain, where a variety of styles take the stage, from very traditional to contemporary and experimental. We wanted to lower ticket prices and tuition costs and get the art form to children. After a few rounds, I found our little clustered series starting to flail as a mid-sized project, unable to scale to move to a bigger theater even though we were selling out the smaller venues. We decided to go big, inspired by the podcast, “How I Built This,” in which the ability to scale was the pinnacle for many featured small businesses. We gathered enough funding to bring a group from Spain and packed the house in 2019. We received publicity for not only putting great artists on stage but also presenting educational activities with integrity. That year, the Atlanta Flamenco Festival spanned four weeks, and we set up a structure that we continue to follow today: something new and fresh in flamenco, as well as something traditional. This helps Atlanta see flamenco as it is presented in Spain, rather than as a stereotype of Spain in the 1930s.

Q: What’s the single biggest misconception people have about flamenco and how have you addressed that in your own work?

A: We are not strippers. We do not dance to mariachi or salsa music. Rather, flamenco is a form of improvisation in which musicians and dancers create a conversation based on non-verbal communication. Sure, at times companies recite choreography or compositions. Even those are based on the rules of our improvisation. And yes, you can learn all of that if you are not from Spain. In fact, Meira and Vergillos have both taught me that some of the most iconic flamenco dancers were Americans, not Spaniards.

Q: What is a typical day like for you?

A: I spend much more time sitting in front of the computer than I would like and much less time dancing than I would like. I fight that all the time. My chair time, about two hours, includes responses to queries for performance and classes that I teach or book for other people, contracting and invoicing, changing the printer toner, repairing the printer, and scouting for grants. I also have to write those grants and final reports. When possible, I meet in person or via video calls with potential partners for artistic project and artistic support, such as photographers. I don't get all of that done in a single day, but I chip away at it to meet deadlines. My studio time, to which I try to dedicate two-to-three hours daily, includes a lot of stretching, technique practice, review of repertoire, and also exploration of new material to try out with musicians. When I have a choreography project, I also have to prioritize setting material for deadlines.

Q: Where do you find inspiration?

A: I find a lot of inspiration in performances. Sometimes I see something new in the tradition, and sometimes I fall in love with something contemporary. That happened last summer in Spain, when I watched Florencia Oz, a dancer who performed with her twin sister and brought the forest and the birds to the flamenco stage in a delicate fantasy. I am still smitten. Sometimes, I hang with musicians and wait for the magic to spark. Sometimes, I cook with my friends. Their jokes make me smile later when I want to express an idea.

Q: Any other interesting projects you have in the pipeline? If so, what are they and when can we experience them?

A: I am working on a video class about flamenco in Hollywood film. Actually, the class was created by Vergillos. I am just the interpreter for the sessions, and I am promoting the class nationwide. I am preparing a session about dance and calculus in the land of arts integration for the GA Department of Education STEAM conference in October, something that I arrived to when I started exploring flamenco rhythms as a teaching tool in K-12 math classes. And, I am setting new work with a tap dancer, which should take the stage in Dallas this year.

For more on what Julie's up to, you can follow her on Instagram at @juliemoondances, @berdoleflamenco, and @atravesarts. Or you can visit her site berdole.com.

Writing prompt: If you could learn anything right now, what would it be and why? What steps would you take to learn it? Could you envision yourself turning this new skill into a new hustle, or side hustle? If so, why? If not, why not?

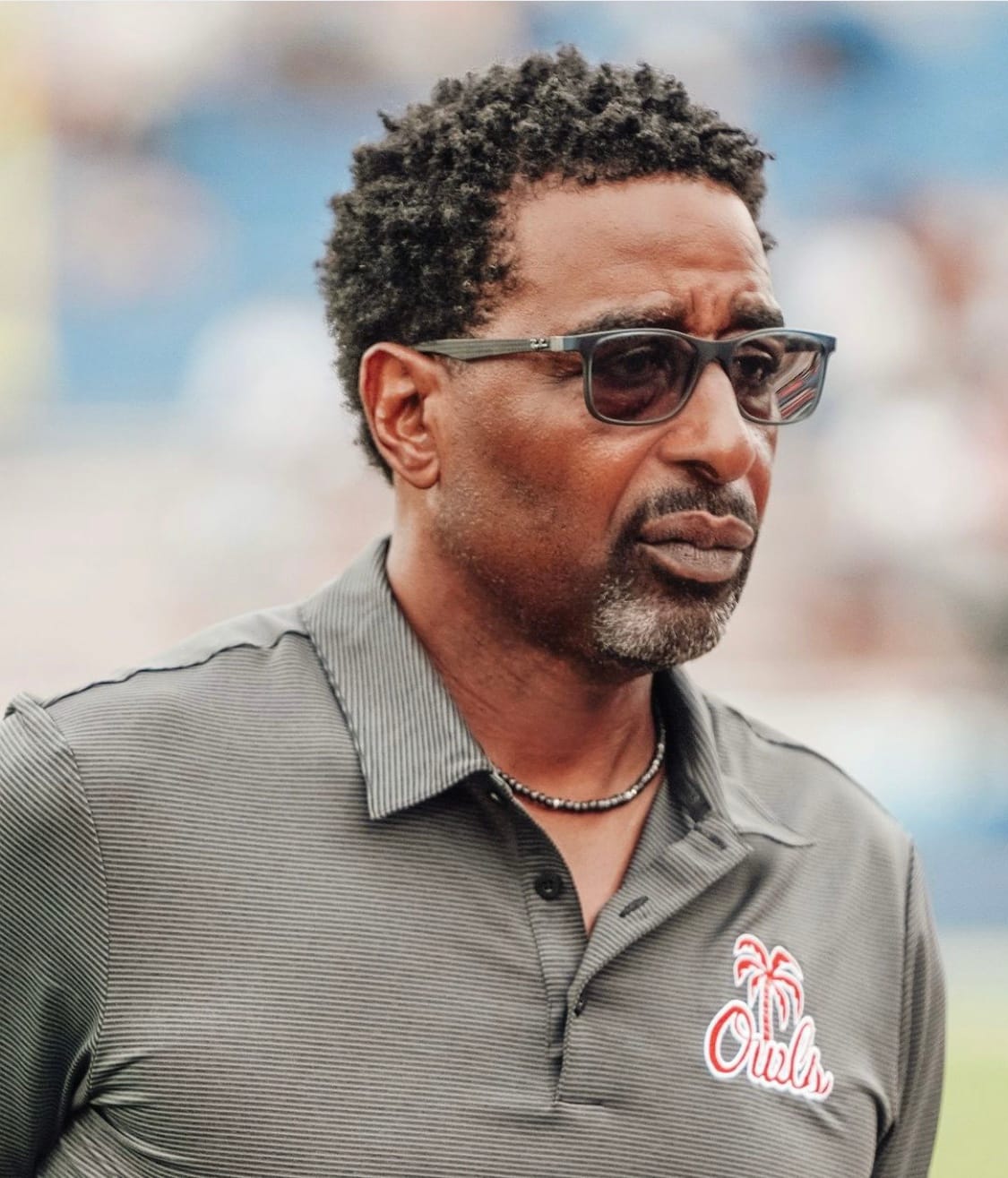

One Wise Owl

In his sixteen seasons as an NFL wide receiver, pro football Hall of Famer Cris Carter racked up nearly 14,000 receiving yards and scored 130 touchdowns. Now, he's mentoring young student-athletes in Florida Atlantic University's football program, trying to push them to be the best they can be on and off the field. For more on Carter's new job with the Owls, click here for my profile on him in this month's Palm Beach Illustrated.

Endnotes

What I'm reading: Writer Nneka M. Okona's Harper's Bazaar exquisite piece about Toni Morrison writing about food in her novels. Please stop what you're doing and take a few minutes to read this. It's very, very good.

Why are people trying to ruin dolphins for me? In the past couple of years we've had orcas ramming into boats, and a movie about feminist sharks in the Seine. Last week The New York Times ran a story about dolphin attacks off the coast of Japan. Fifty or so people have been attacked over the past three years, and some scientists say it's the work of a lone dolphin who is, um, looking for love in all the wrong places. As a longtime dolphin enthusiast, I really don't know what to make of this. Part of me feels like I may never look at dolphins the same way again (since apparently they aren't looking at us the same way either). Part of me realizes that as beautiful and powerful and friendly as they are, we need to resist that urge to get close, and appreciate them from a safe distance.

Where I hope you'll donate this week: I dropped the ball on this last week because I was wee bit preoccupied, so apologies. This week, if you're game, I'd like you to head over to Whale and Dolphin Conservation North America and think about either donating what you can to help their work, or adopting a whale or dolphin. Why? Because it's fun, and it helps these beautiful beasts, too. So, please if you can, consider a gift.

Paige Bowers Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.