Myriad Little Rebellions

"Have no illusions. These men are not tourists." -- Jean Texcier

A look at Occupied France in 1940, an escapist memoir about the good life, playful narwhals, and a little reminder from The Queen of Soul.

Hello beautiful readers,

How are you doing?

I spent part of the week preparing for a podcast interview about my first book The General's Niece: The Little-Known de Gaulle Who Fought to Free Occupied France. It's the first English-language biography of General Charles de Gaulle's niece, Genevieve, who was a teenaged resistance fighter during World War II, a concentration camp survivor, and then a public figure in her own right after the war. It is hard for me to believe that this book is almost ten years old, and equally hard for me to believe that 80-some-odd years after some of the events in it took place, we still haven't learned a damn thing from them. But I am grateful that I was able to speak about that moment...in this moment. The interview should be available a month from now, and I'll share it here once it goes live.

In the meantime, I wanted to share a condensed passage from the book about why and how young, bookish Genevieve de Gaulle found her way to fight for France. In later years, she would say her first acts of rebellion were trivial, and she hesitated to even mention them. But for her, and others, these symbolic acts were confidence builders that led to something much bigger and bolder. I hope this little-known de Gaulle inspires you to be brave this week, and all weeks. After all, we're all out here fighting some sort of battle, right?

Be kind to one another and bon courage,

Paige

A Gathering Sense of Purpose

Genevieve wondered what to do next. She never saw herself as a gun-toting warrior. As smart as she was, it was difficult for her to know how to channel her exasperation about the war into something useful. She considered her next steps as she ambled around Paimpont's quiet streets, wearing demure white blouses and well-tailored skirts that billowed gently in the warm summer breeze. Nazi soldiers who patrolled the town during the summer of 1940 saw her as an innocent-looking young woman, a little slip of a thing who was lost in thought and, perhaps, on the way to run a simple errand for her mother. If they had looked more closely, past the head of soft ringlets that framed her face, they would have seen that she bore an unmistakable resemblance to her now-notorious uncle: the deep-set eyes, the long and prominent nose, the taciturn mouth that spread into a slow, shy smile that concealed a gathering sense of purpose about the unwelcome young men at the end of her gaze.

By the end of that summer, Genevieve grew so tired of seeing German soldiers that when they passed her on the street, she turned her back on them without saying a word. For someone who did not know where to begin and who typically did what was expected of her, it was a small step. But all small steps lead somewhere, no matter how timid they might seem at first. For those who refused to accept the terms of the June 22 armistice and the division of the country into a northern occupied zone and the so-called southern free zone, these myriad little rebellions connected likeminded people and emboldened the fearful to enter the fray. It was like raindrops on a windowpane; each drop hit the glass, joining another, and then another, before building into a larger stream of water with momentum.

In the occupied zone there was much to wash away. German soldiers were omnipresent in their drab, gray-green uniforms; they were in the streets, the shops, the cafes, and the museums in Paris. They marched down the Champs-Elysees, singing Nazi songs. They hung swastikas and placards in Gothic script on all public buildings. They commandeered private homes and luxury hotels for their own use. They changed the clocks to German time. Gone were the tricolors that once snapped in the breeze. There were curfews and food rations and other restrictions that grew with each passing day. It was difficult to know how to respond to this, in part because it was hard to know how long these conditions would last. The journalist Jean Texcier circulated a tract called "Tips for the Occupied" shortly after Nazi troops first arrived in the capital. Among Texcier's recommendations: be polite to the Germans but not too helpful, as they won't reciprocate; show confusion if the Nazis address you in their native tongue; and politely let German troops know that what they say does not interest you. "Have no illusions," Texcier added. "These men are not tourists."

The German presence became so overwhelming that for many of the French it made sense to support Marshal Philippe Petain's government, which was now headquartered in the spa town of Vichy. Petain had saved the country once, they felt, and protected it from the worst. Surely he would do the same again. On July 10, 1940, France's parliament voted to give the marshal full powers so that he could begin a new French state with Pierre Laval as his second in command. Laval had been instrumental in getting the government to remain in the country and accept an armistice. He was convinced that the Germans would emerge as the ultimate victors in the war and because of that France would be best served to collaborate with them. He pushed those views on Petain, who for many embodied the country's sovereign power. Meanwhile, the marshal called for a national revolution centered on work, family, and country. Reconnecting with these humble traits would restore France's strength and security, he said. The nation had liberty, equality, and fraternity to thank for its swift decline.

Charles de Gaulle stood in London and offered himself as a viable alternative to Petain and capitulation, asking all Frenchmen who wanted to remain free to listen to his broadcasts or join his side. On June 28, 1940, the British government recognized Charles de Gaulle as the leader of the Free France movement and furnished him with the loans, grants, office space, and broadcasting facilities that he needed to build support for his cause. For those who hungered to united with him, it was no small feat. It required leaving France and facing exile, criminal charges, and even physical danger. Some viewed leaving for England as shameful, especially when France was faced with such hardship. Ever mindful of the historic enmity between the two countries, Nazi propagandists began whispering that de Gaulle was nothing more than a British puppet who would make France part of England.

Not everyone bought the lies. "Your voice is the only one to speak out firmly and clearly," one school headmistress wrote General de Gaulle. Others wrote that he had "awakened France" and restored "the morale of Frenchmen." They pinned their hopes on him, awaiting him as if he were the Messiah. But their savior was a country away, separated from his family and without considerable forces at his disposal.

As for Genevieve, she, like other students, began tearing down Nazi posters and cutting out small Crosses of Lorraine, which had become the symbol of resistance. Genevieve and her friends printed and distributed anti-Nazi and anti-Vichy leaflets, but they always had the sense that there was more to do. They were young, single, and had little to lose. Late one night they crept to a bridge that spanned the Vilaine River so they could tear down the Nazi flag that hung from it. It was after curfew, and Genevieve proudly scurried back with the crimson flag in her arms. It was her first spoil of war.

But pilfered flags wouldn't topple a regime. "The first things [I did] were similar to what most of the French were doing," she later wrote. "They were symbolic, almost ridiculous, and I hesitate to mention them." She and her peers began wondering where they should go to best serve the nascent underground movement. Some felt they'd see the most action if they joined General de Gaulle in London. But Genevieve believed she'd be most valuable in France, and she decided to move to Paris to continue her history studies at the Sorbonne As she traveled toward the capital, Genevieve de Gaulle knew her real fight had just begun.

Writing prompt: Think of something that you feel is worth fighting for. What is it, why is it important to you, and what are you willing to do to stand up for it?

Protesting with Paint

Some tore down Nazi placards and flags. Others circulated pictures of General de Gaulle. The rest did things like blowing up rail lines, gathering intelligence, and shepherding downed Allied pilots to safety. There was no one way to resist during wartime. For one young student, Francoise Gilot, resistance meant capturing the moment with her paintbrush in a way that seemed like an innocent still life, but was truly so much more.

"In 1940, when the defeat of France shattered the pride and hopes of an entire generation of young French people, I felt that upholding the cultural values we shared was an individual duty and a necessity," Gilot later wrote. "I looked for a way to bear witness, and express my thoughts and feelings clearly and yet in a manner that would remain enigmatic to the Nazi occupants. A fish on a plate, its head severed, blood dripping from its entrails next to a kitchen knife could evoke the horrors of war: the fish itself is a symbol of Christ or of any victim."

In the painting "The Hawk," there is a taxidermied bird of prey in the foreground, likely symbolizing Germany. In the background, there are tombstones to symbolize the graveyard France had become. The bird, meanwhile, is locked inside, and in the distance, the Eiffel Tower rises above the scene as a symbol of hope rising above the hawk's oppression.

"In a way, I think that art is like the Olympics," she said. "You have to break a record. So that means something more simple, more astonishing, the need to go further in some direction, to break through, to create freedom."

Be your own artist, and always be confident in what you're doing. If you're not going to be confident, you might as well not be doing it.

--Aretha Franklin

Endnotes

What I've been reading: Many people extol the virtues of Paris in spring, but I really love it in winter, when the crowds aren't as crazy, and the twinkling lights and slate-colored skies make everything feel just that a bit more magical and serene. You've probably sensed that I haven't felt incredibly serene lately, which is why it was nice to lose myself in David Coggins' Paris in Winter: An Illustrated Memoir. This book is a stroll through the people, places, culture and history of the French capital, as it was experienced during Coggins' near-annual family trips. It's a ode to one of my favorite places, and to the pleasures of slowing down and savoring beautiful moments with the people you love most. 15/10 would recommend. Next up: Laila Lailami's The Dream Hotel.

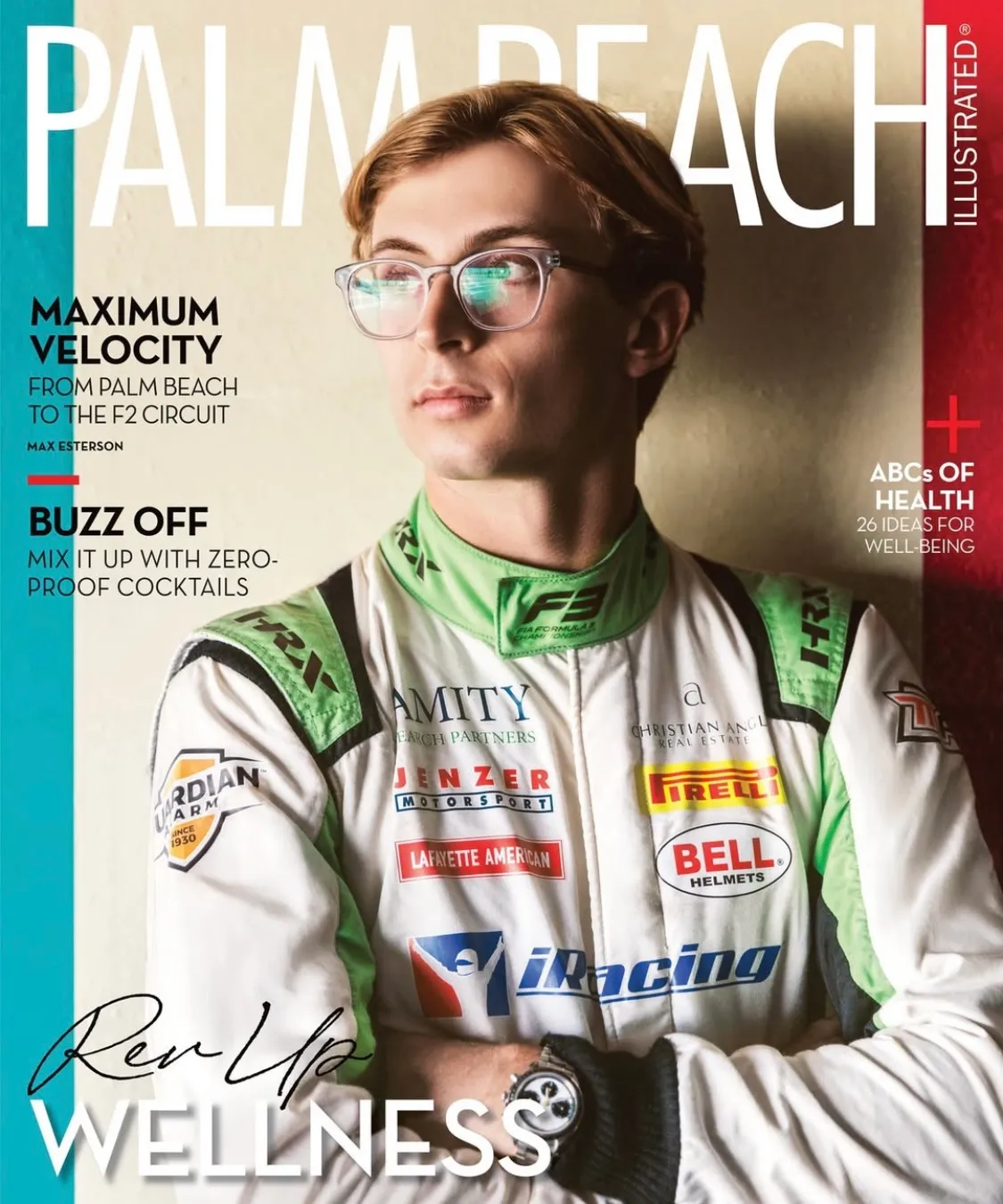

What I've been watching: Season seven of the Netflix F1 series Drive to Survive, even though I haven't seen seasons one through six. At the risk of spoiling this for you, people drive fast, there's a ton of drama, and only one Spice Girl.

Fun fact: Narwhals play with their food.

Another fun fact: Los Angeles' first female police officer patrolled the city with only a badge.

If you're in Atlanta and looking for something to do this weekend: don't miss "Sandy Powell's Dressing the Part: Costume Design for Film," which is in its final days at SCAD FASH. I've seen the exhibit already and it's incredible from start to finish. You'll find her designs for the 1992 film "Orlando" (my favorite piece was the gown she created for Queen Victoria, played by Quentin Crisp), as well as costumes from movies that include "Shakespeare in Love", "The Crying Game", "Gangs of New York", "The Aviator" (that slinky gown Gwen Stefani wore as Jean Harlow is here), and "Mary Poppins Returns." What I liked about seeing these works in person is that you can catch little details you might have missed in the theater, like the delicate little butterfly details around the neckline of Cinderella's ball gown, or the painstaking floral embroidery on Anne Boleyn's black velvet dress.

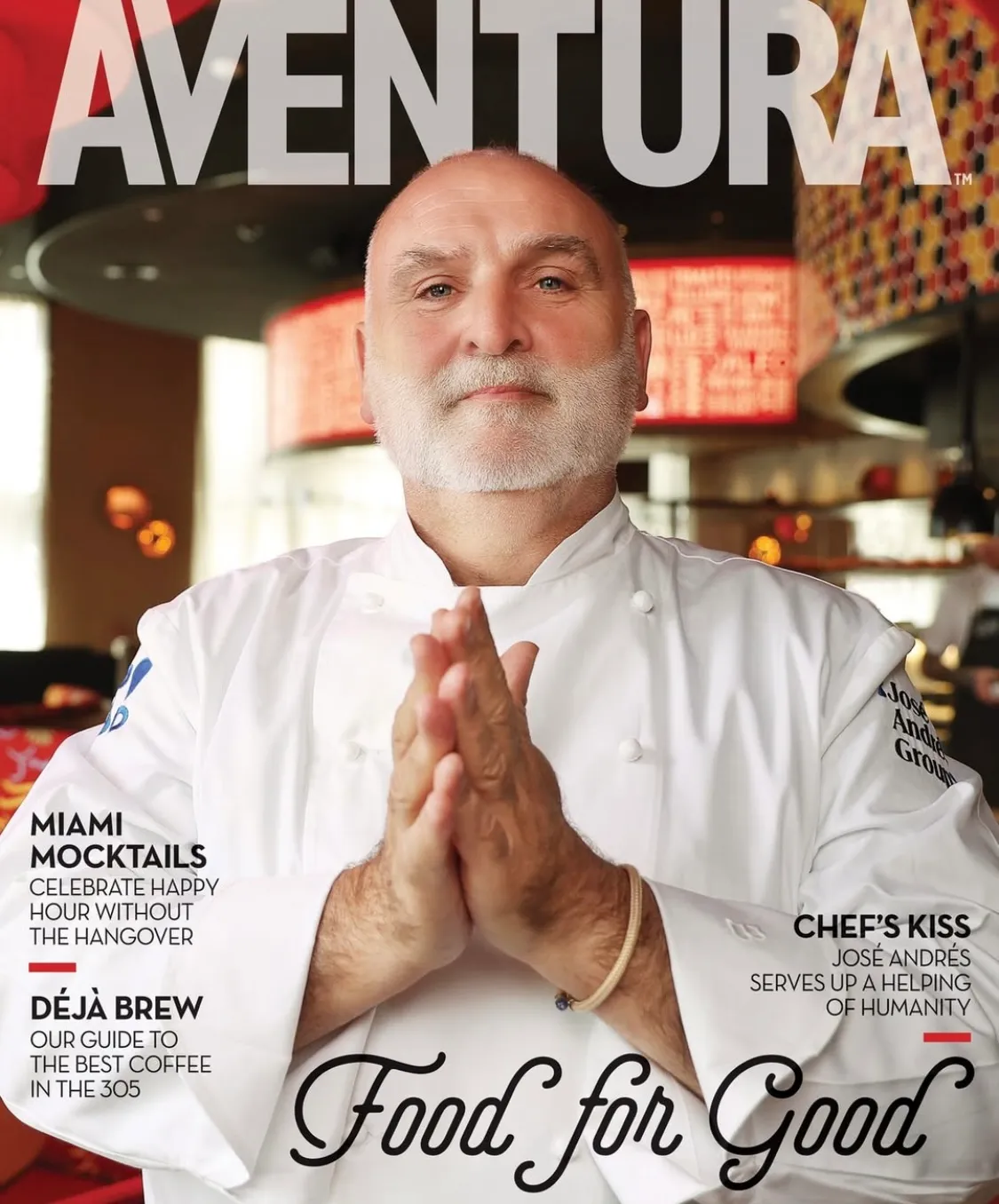

Where I hope you'll donate this week: I’ve been devastated watching the scope of destruction and suffering in Gaza and the West Bank over the last year and a half. In Gaza alone, 85% of the population has been displaced, tens of thousands have been killed and injured, and there are no longer any fully functional hospitals. That’s why I’m participating in AUTHORS AIDING PALESTINIANS, a fundraiser benefiting @aneraorg, a non-profit providing essential food, medicine, and supplies to displaced Palestinians. The fundraiser will run today through Sunday 3/16, and you can donate to it via the fundraising link in my Instagram bio. During this time of Ramadan, all donations will be matched. I hope you’ll join me in donating to this worthy cause!

Paige Bowers Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.