Patchwork

Quilts, prints, singers and reading for health.

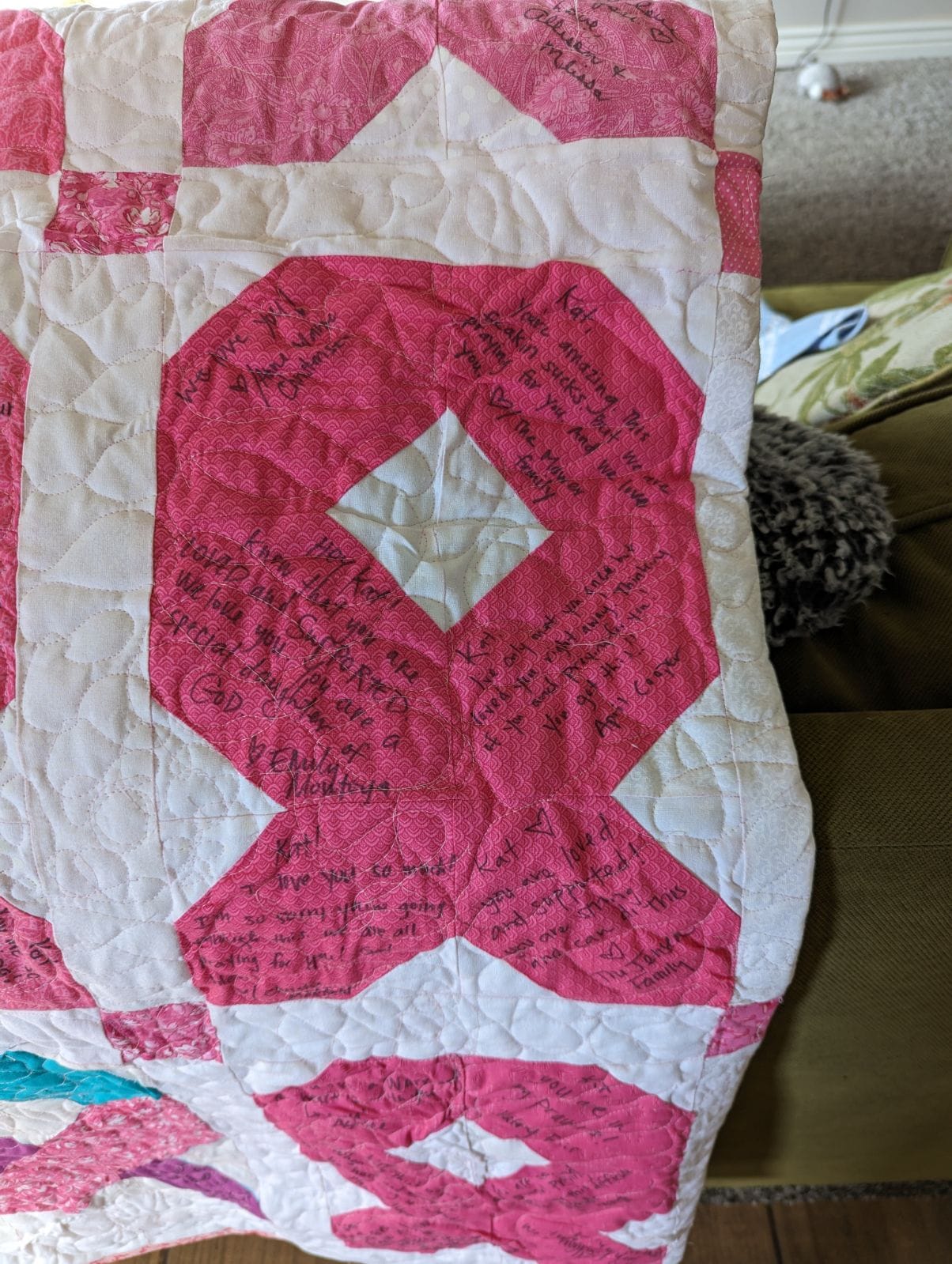

This past weekend was my sister’s birthday. A lovely group of women in her neighborhood brought her some vegan cupcakes and gave her a beautiful quilt that they made. It was an incredibly moving gesture, one, because they knocked this gorgeous quilt out in just a few weeks, and two, because they got other neighbors to write their messages of love and support on it.

I am so grateful that my sister has neighbors like this. One of them told me that when I come to visit, she'll show me how to quilt. I'm not sure if I'm patient enough to become a quilter, but I do truly appreciate all the detail work that goes into making something that's not just practical, but a work of art.

Which brings me to the quilters of Gee's Bend, Alabama. For them, quilt-making began as an act of survival...

Just as the Great Depression hit the remote, rural town of Gee's Bend, Alabama, a merchant who had been offering credit to local sharecroppers died. Though circumstances were already dire for Black residents, the merchant's family took all of their food, animals, tools and seed to resolve the debts. With winter looming, the Red Cross distributed food rations so these families wouldn't starve. As temperatures dropped, food could only provide so much comfort. Black women in the community began making quilts with whatever bits and scraps they had on hand. The goal was not to wind up in an art gallery (though they would do that much later), but to keep their friends and families warm. Arlonzia Pettway, the daughter of one of these early quilters, recalled in an documentary that after her father died, her mother said she would take his work clothes, "shape them into a quilt to remember him, and cover up under it for love."

The striking geometric patterns these women stitched onto their blankets were passed down generation after generation, and like their creators, survived their share of disasters and heartbreaks. When Black Gee's Bend residents lost their jobs and homes after registering to vote in 1966, an Episcopal priest and civil rights worker named Father Francis X. Walter believed that selling the beautiful quilts he had seen drying on Black women's clotheslines could improve their economic circumstances. With the help of several volunteers, Father Francis established the Freedom Quilting Bee, a cooperative business that poured the proceeds from quilt sales into the local Black community. Over time, the quilters became nationally acclaimed for their work, which The New York Times called "some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced." Today, you can see the quilts in acclaimed art museums or buy them on Etsy, which has interviews with the creators. Though the town of Gee's Bend (which is now also known as Boykin) is home to less than 300 people today, its artisans continue to teach younger relatives how to create the pieces that put the town on the map. May the rich tradition endure.

Writing prompt: What is something you learned from an elder that you want to pass down to other generations – or teach other people to do — so that it will endure? Who taught you this skill and what are your memories of that moment? Why do you think this skill is important to pass down? What do you learn or gain from knowing how to do this particular thing? Does it make the world a better place in any way, shape, or form?

Female printmakers in the 1930s

Week after week, I never know how this newsletter is going to turn out. I make lists of story ideas and thoughts. Sometimes those items wind up here. Sometimes they stay put on the list until I figure out what to do with them, or how something will fit together with something else, or whether that even matters at the end of the day. For me, the goal is to give you a little something to read during your lunch break, or any other sort of pause in your day.

A couple of weeks ago, I signed up for a panel about women artists in the 1930s. Right now those little-known women are having a moment in museums across the country and a panel of curators got together to explore how their work captured the moment in which they were living, and why that work has special relevance now. Where the ladies of Gee's Bend created pieces that helped them survive hard times, artists like Elizabeth Olds portrayed those hard times in their prints as part of the Federal Art Project (FAP). FAP was a relief program during the Great Depression that employed around 10,000 artists to create public art without any restrictions on subject matter or style. Printmakers alone created some 240,000 works that captured strikes in action, miners at work, families trying to make ends meet, and more.

"There are so many reasons why printmaking took off in this period," said Alison Rudnick, associate curator of the Department of Drawing and Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. "One, more artists had access to tools, equipment and training through [FAP] to make these prints. And the second reason is that because this is activist art that is being made for the public, it can be executed in multiples and circulated widely."

For artists accustomed to working in isolation, the FAP era was a period when they could come together in workshops to talk about their ideas with peers and experiment. Through these conversations they expanded their ideas about labor, infused their works with images of women and people of color, and raised questions about the whole notion of the American Dream.

"This wasn't covered in great depth when we were students," said Virginia Anderson, curator of American Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art. "But as we approach it with fresh eyes now, we can look at these pieces and see so much that is just like today."

The Harry R. Ransom Center is currently featuring a show of one FAP-funded artist, Elizabeth Olds, who was the first woman to be awarded a Guggenheim fellowship for the study of visual arts. After her experience creating federally-funded pieces during the Depression, she authored six children's books. She believed in art's power to educate.

For more about women creators during the Depression, check out this piece on Women Arts, or this one from the Harn Museum of Art.

As you probably know, Paris is hosting the Olympics this summer, and because it's Paris, that opening ceremony is really going to be something to see. However reports that French-Malian songstress Aya Nakamura might be singing an Edith Piaf song to open the ceremony have ignited a furor in the country about language (Nakamura's hit tunes often involve a creative fusion of French with English, Arabic, and West African dialects) and race (the Paris prosecutor's office has opened an investigation into racist insults that have been hurled at Nakamura online). For more on this story, see this. And Google her music. She's a hitmaker and one of France's top cultural exports for a really good reason.

Read your way to wellness

Let me begin this by saying the royals have been in the news a lot lately, so I apologize for giving you even more of what none of us want. But this is one of the rare instances where some crown-wearer carried on about something that was particularly meaningful to me. This week, Queen Consort Camilla, celebrated a new research study which found that five minutes of reading a day reduced stress by almost 20 percent and improved concentration and focus by as much as 11 percent. It also found that reading earlier in the day helped people feel more connected to others and better able to tackle any challenge they might face.

"Just as we suspected, books are good for us – and now science is proving us right," she said.

As if you needed another reason to head to your local, independently owned bookseller to grab something new.

All curled up...

Boots hasn't appeared here in a couple of weeks, and he thought you might be missing him. He sure missed you. So here he is, curled into a little Bootsy pie. Don't you just want to pet his velvety ears?

Boots wants to know who your pet friends are and what they like to do. Send us a pic of your pet and their story if you like, and we might just feature them in a coming letter.

What I'm happy about: THE DECATUR BOOK FESTIVAL IS BACK, BABY! I CAN'T WAIT FOR OCTOBER!

What I'm reading: Chasing Beauty, Natalie Dykstra's acclaimed new biography of Isabella Stewart Gardner.

What I'm listening to: Beyonce's new Cowboy Carter album, because I am a lot of things, and one of them is predictable.

Where I hope you'll make a donation this week: About two years ago, "60 Minutes" aired a story about an Air Force veteran named Fredrick Miller, who bought a grand old residence in his hometown where he could host gatherings for his extended family. One thing led to another, and he and his family learned that this home was a former tobacco plantation where their ancestors were enslaved. I've come to know Fred over the course of the past year and the story of the house is just one part of a rich and inspiring story about an American family. Fred is trying to raise money to preserve a slave dwelling on the property and turn a slave cemetery full of unmarked graves into a more peaceful and dignified resting place. So, please, if you can, help him preserve this important bit of history by making a donation to the Sharswood Foundation.

Thank you for allowing me to visit your inbox each Friday with these tidbits. If you know someone who might enjoy this newsletter, please share it with them and encourage them to subscribe for free. Each week(ish), I'll be sharing an eclectic range of stories and so forth. Sometimes I'll throw in a little bit of writing advice, and answer whatever questions you may have. It's a work in progress, rooted in my passion for writing about history, people from all walks of life, and the various things that interest me. Having said that, please don't hesitate to reach out with any feedback or suggestions for other things you'd like to see here. I want this to be a little weekly treat full of things you might find interesting, entertaining, inspiring and maybe even helpful, too!

Paige Bowers Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.