Ripley

Hot priest goes creepy on us, the delights of Dutch art, and...pantry moths.

When The Talented Mr. Ripley came out in 1999, I went to see it in theaters because it had a good cast (Matt Damon, Jude Law, silly Gwyneth Paltrow) and it looked like it was beautifully filmed. I hadn't actually read the Patricia Highsmith book on which it was based. I didn't know that the story had been adapted for film at least five times before then. I also didn't know that I was getting myself into something that was not merely pastel hues and the fun and romance of expat living, but rather something much, much darker.

Here's the gist of it: Rich father in New York City is fed up with his son, who is goofing off in coastal Italy on his dime. So he hires a private investigator to find one of his son's friends, and convinces said friend – Tom Ripley – to go to Italy and convince his son to come home. Ripley is a con man, so you kind of have to wonder about any private detective who doesn't find that out. But, fine. The dad hires Ripley, and Ripley heads to Italy to lure the son, Dickie, back to the States. But Dickie isn't about to do that. He's got a beautiful girlfriend – Marge – and a really good life painting very bad paintings. So of course, Ripley falls in with this pair, then falls in love with the life they're living, and decides that maybe (okay, definitely) he wants that life too. I mean, who wouldn't want to spend their days in the sun, finding any old reason to raise a glass? Tom is not dumb. He is deeply in touch with the elemental human quest for something better. But Marge doesn't trust him, and Dickie grows weary of his company.

That's when stuff starts going sideways. The reason why I love Ripley, Netflix's brand-new series so much more than the 1999 film, is because it is beautifully filmed in black and white (which enhances the creepiness and almost makes you feel like you're in the middle of what's going on), and develops Ripley's character over eight episodes in a way that is utterly chilling. Andrew Scott, who played the "hot priest" character in Fleabag, is the insidious Ripley we've deserved all along. He is so riveting, charming and monstrous, and so slippery and manipulative. It's an unforgettable and unsettling performance that gets at the psychological complexities of one of literature's great antiheroes, and I hope you'll take the time to check it out.

In the meantime, if you're wondering who could have come up with such a tale, here's an interesting story about author Patricia Highsmith, who was apparently just as, um, interesting as Ripley.

Write what you know, I suppose.

Writing prompt: If you were to write what you know, what would that look like? Go into as much sensory detail as you can, even about the parts of your story that give you pause. Does putting the harder-t0-talk-about elements on the page provide you with any sense of relief or do you want to lock them away somewhere for safekeeping? How would sharing the hard things help someone else feel less alone?

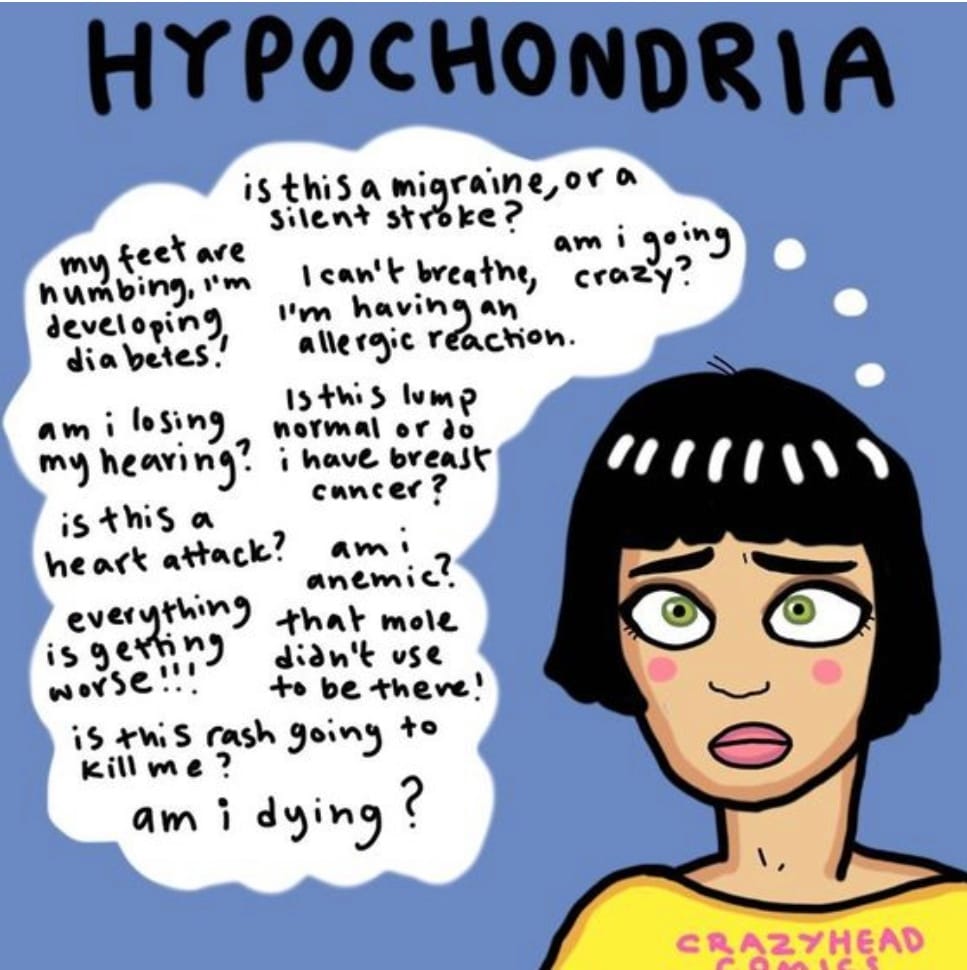

Writers and Hypochondria

Hypothetical situation, maybe: Paige meets Michelle at a wine festival. Michelle is dropped off at said festival by her sister, who is recovering from COVID. Paige is fixated on this because Paige has not had COVID (knock wood), and desperately wants to know whether Michelle's sister is no longer testing positive because if she is still testing positive, Paige definitely sees a situation where she, herself, could not only get COVID, but a battery of other things too. Then somehow one thing will lead to another and you'll all be crying at my funeral.

So...I have reached the point in my life where I accept that I have a touch of hypochondria. Okay, maybe more than a touch. I enjoyed this LitHub piece about whether writers are more prone to it, or whether we just know about their neuroses because they commit them to paper. The piece stems from Caroline Crampton's new book, A Body Made of Glass: A Cultural History of Hypochondria, which fuses together literary criticism, memoir, and cultural history to explore the topic and its impact on our physical, mental, and emotional health. Though my to-be-read pile is gargantuan, I plan to pick up Crampton's book to see how she tackled hypochondria, and arrived at the conclusion that it's about our attempts to fight uncertainty with the comfort of a good, fact-based explanation for what is really going on.

Going Dutch

You know what's awesome? Going to the High Museum by yourself right when it opens, and especially on a rainy Sunday. You beat the crowds and you can take a little more time with the paintings, which is great because this new "Dutch Art in a Global Age" exhibit is one of those things that you need in your life. Trust me.

The exhibit, which opened last week, shows how this little country became rich from trade and how that wealth changed Dutch society and fueled an artistic boom. But it also acknowledged the role that Black lives played in building that wealth, which makes you look at all these achievements differently. Between 1612 and 1814, the Dutch West India Company trafficked about 600,000 men, women, and children from West Africa to plantations in Brazil, Suriname, and the Caribbean. Meanwhile, the Dutch East India Company took somewhere between 44,000 and 67,000 enslaved people to territories across Asia to harvest spices, coffee, and sugar.

Yes, there were extraordinary paintings of maritime scenes, cityscapes, people and tables heavy with flowers, porcelain, and amazing things to eat. There were Rembrandts galore. But this lone – and rare – portrait of a young Black man really stood out to me in this sea of wealth and luxury. First of all, it was beautifully rendered. But at the same time, the caption on the piece attempted to reduce this young man to a generic African hunter, even though he was likely part of a small community of free Black people who lived in Amsterdam. His face is full of personality, warmth, and hope for something better. It's an important narrative within the larger tale presented here, and I think without it, the whole exhibit might have felt incomplete.

Anyway, go see it if you're in Atlanta, or plan to be. It's at the High Museum of Art until July 14.

Endnotes

What I'm happy about: Tuesday night my husband and I went to Truist Park for the second game in Atlanta Braves' series against the Miami Marlins. I haven't been to batting practice in ages, but Marlins second baseman Luis Arraez kindly invited me and my husband to watch batting practice on the field about two hours before the game. Now that was fun. They call him "La Regadera" (The Sprinkler) for good reason. In batting practice, he sprayed his hits first to the right, then to the left, then to dead center before trying to pound a homer on the last pitch he got. During the game, he went 2 for 4, slicing one hit into right field and his final at bat into left. The Marlins lost, but we had a good time, between the perfect weather and the Fox Bros. BBQ pulled pork sandwiches. Many thanks to La Regadera for being such a nice gent to us. His mama raised him well.

What I'm not happy about: Pantry moths. I thought I wouldn't wish these on my worst enemy, but late last week I decided that I would absolutely wish them on one particular person, and for good reason. The rest of you are in the clear (and also, I love you very much).

Another thing I'm not happy about: Atlanta United blowing leads. First, they tied stupid Philadelphia. This past weekend, they were winning by one. Then "head coach" Gonzalo Pineda pulled midfielder Tristan Muyumba (one of my favorite players, how dare he?), and FC Cincinnati scored two goals in rapid succession.

What I'm looking forward to: Al Franken standup show with my dear, darling Michelle at City Winery on Saturday night.

What I'll be celebrating: Nineteen years of being a mom to the world's most awesome person on April 29. If I've done anything right, it is this kid. Period. I love you so much, Avery!

Where I hope you'll donate this week: The Prison Book Program provides people in prison with free books and other reading materials that meet their specific needs and interests. You can either donate your own books to a state-specific program, or you can buy new books that people have requested from these lists. When Malcolm X was incarcerated, he said reading changed the course of his life, adding that it "awoke inside of me some long-dormant craving to be mentally alive." Please consider a donation, if you can, as the program has been a life-saver and life-changer for so many.

Next week's issue: I'm kicking it off with the fabulous and whip-smart CEO of MUTHA, Hope Smith, who I recently interviewed for a cover story. I think you'll enjoy meeting her, and I KNOW you will enjoy the photos that accompany this piece. So stay tuned, and if you have a friend or friends who you think might enjoy this weekly bit of goodness, please do tell them to subscribe for free.

Paige Bowers Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.