The Things We Tell Ourselves

A helpful old man, an update on the Seine, and a call for your favorite books right now.

The headlines have really been something lately. Life has too. I don't know what to say about any of it, so I won't say anything, because sometimes things really don't need to be said. What I will ask you, fair reader, is how you're holding up and what is getting you through these moments. Is it coffee with a neighbor? Watching the eight new "Bluey" mini-episodes that were just released? Exercise? Screaming obscenities into the void? Something else? Let me know.

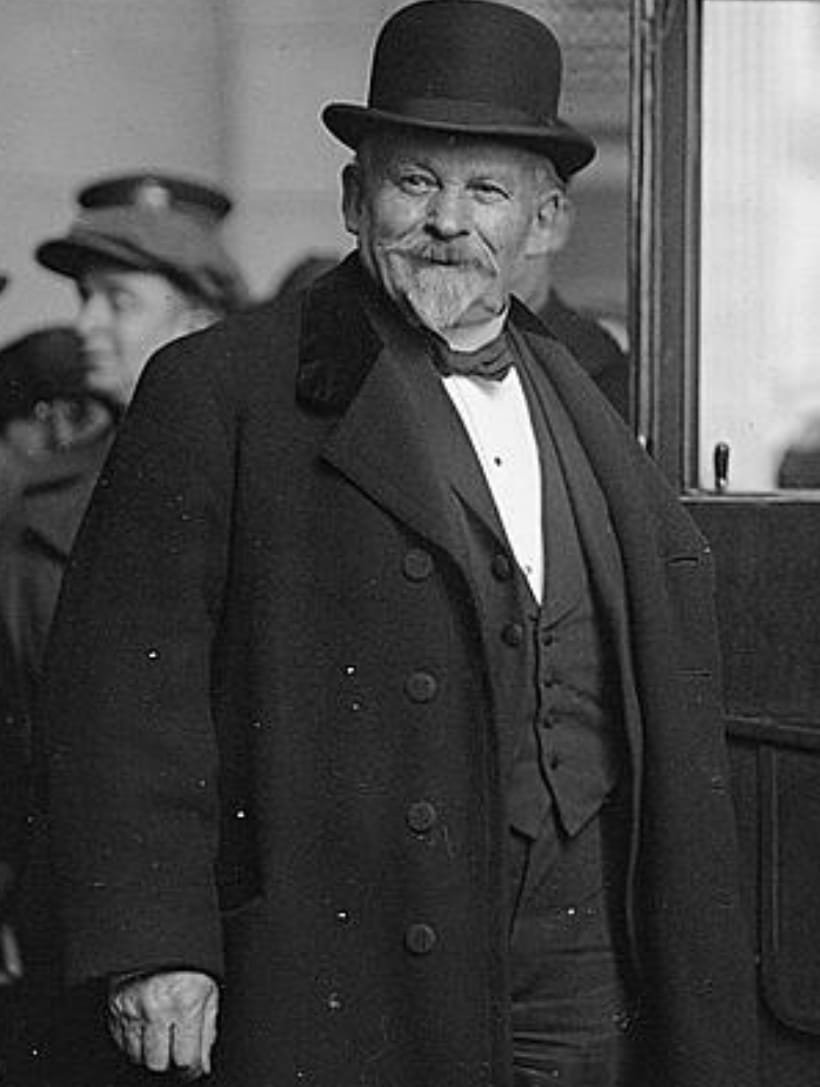

Today, I wanted to kick things off with this little piece of writing I did about a cheery old man who did not trouble vast swathes of humanity. Rather, he arrived in America a little more than a century ago to teach its citizens how to cure themselves of their own angst and ills. What a novel concept. His name was Émile Coué, and by the time he stood before a gaggle of reporters in a crowded ship cabin, his reputation had preceded him, for he had already gained renown in Europe.

Let's take a trip back in time to January 4, 1923...

Émile Coué was enjoying a leisurely breakfast in his cabin on the RMS Majestic. His journey to the United States had taken two days longer than anticipated because of strong winds, rocky seas, and then a raging snowstorm that greeted the ship just as it neared Manhattan the night before. Visibility being what it was, the captain dropped anchor, rather than steer the vessel up the Hudson River. When the engines stopped at 8:49 p.m., Coué tucked himself in for the evening so he could be fresh and vigorous the following day. Now, in front of his morning meal, the elderly Frenchman cheerfully steeled himself for what lay ahead. Forty journalists awaited him in his friend the Marchesa Capponi’s suite. Scores of photographers clamored for a portrait of him on the ship’s icy deck. Countless anxious, ailing people hoped that he would reply to their telegrams, and more importantly, heal them.

Coué had never healed anyone. Nor had he claimed he could. But over the years some patients likened their experiences with the retired pharmacist to a pilgrimage to Lourdes. The tales of the blind he helped see and the lame he helped walk only enshrouded him in the sort of mystical sparkle that muddied the simplicity of his mission. Coué had come to the United States to teach people that with practice, they could unleash the power to heal themselves or at least improve their overall well-being. To do this, they had to utter a simple phrase twenty times in the morning and twenty more times before they went to bed at night: “Every day in every way I am getting better and better.” They had to say it with conviction, as they kept track of their repetitions with a rosary of knotted red string. This hypnotic act was called autosuggestion, and increasingly, The Coué Method, after its originator.

In England, he had already won over some prominent acolytes, among them Lady Ethel Beatty, the American department store heiress who had read of his work and brought him to her adopted country for a speaking tour. There was also Lord Curzon, British secretary of foreign affairs, whom he had cured of insomnia in three nights. And there were Julia Marlowe and E.H. Sothern, two prominent Shakespearean actors who were treated for undisclosed ailments at his clinic in northeastern France. American doctors were reserving judgement about his much-discussed methods, figuring there would be no harm in what had been billed by his manager Lee Keedick as a mere lecture tour. If Keedick promoted speakers like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, H.G. Wells, Ernest Shackleton, and Queen Marie of Romania, there was no reason to believe that he would torpedo his reputation on an old man in a baggy three-piece suit. As long as Coué didn’t set up clinics run by laypeople – and there were plenty of rumors about that – everything would be okay.

Coué had sailed to the United States on a tidal wave of interest, arriving in New York City as the elements seemingly conspired to thwart him. He was not to be deterred. Not by ice, not by snow, not by anyone. He had made up his mind. Three days prior to his arrival, there had been advertisements in The New York Times hailing his visit and announcing that his books – and others written about him – would be available for purchase in metro-area bookstores. Another ad celebrated how he had helped many people gain a new and brighter outlook on life, and so newspapers would begin syndicating a series of articles written by him.

“You can read them in The World – and in The World only,” the ad read. “This may be the great opportunity of your life.”

It was a big break for Coué too. After finishing his breakfast, he left his cabin and ambled into the Marchesa’s suite, eager to begin spreading his ideas to an entirely new audience. Before he took any questions from reporters, his publicist handed each reporter a mimeographed sheet that read:

“I come not as a miracle man, but as the humble bearer of a useful message; not as a doctor, but as one who would be a teacher and help mankind in a practical way. Much has been said about the method for self-betterment which I advocate and which I endeavor to teach to others, but it is so very easy to pass over the invisible line into sensationalism and to bring discredit to an otherwise sound and unassuming theory…I know of no better way for showing my appreciation than to seek for a clear understanding with the public at the very beginning, and ask for its calm judgement after I have had opportunity to explain my work. I am not the bearer of a new message, because for many years it has been known that the subconscious mind is able, through an exercise of the imagination to overcome the conscious mind in the exercise of will-power, in the accomplishment of betterments.”

He did not wish to challenge medicine or surgery, he explained, and he was not offering an alternative to organized religion.

“If, however, I can succeed as I have done many times in the past in helping others to understand themselves and exercise their minds so that they can improve their physical condition and achieve better health and happiness, then I shall have lived up to the full letter and spirit of the only claims I have ever made. Self-mastery, through conscious autosuggestion, is the full limit of my message and there is no mystery attached to it or myself.”

And with that, the questions began. Did he intend to open an institute in New York? How did he develop his theory? Should the medical profession object to his work? Can his method be used in prisons to combat criminal behavior? Coué stood there in his stiff white shirt and bowtie, puffing on a cigarette as he answered each query.

“Were you seasick?” another reporter asked.

Amused, Coué cocked his head to the side and smiled at the journalist.

“You are laughing at me,” Coué said. “If you use autosuggestion every day you become stronger and stronger and that is why you aren’t subject to seasickness. I have had letters from persons telling me that they have noticed this. For me to have been seasick on this trip would have set a horrible example!”

The reporters were charmed by his reply.

His host, retired engineer Oliver S. Lyford, told reporters that every effort would be made to prevent Coué from overtaxing himself during his trip. There would be lectures, which were already sold-out, and no one would be able to have a personal meeting with him. Lyford then announced Coué’s schedule for the following day: a visit to French Consul-General Gaston Liebert, followed by a tour of the city that included a trip to the Bronx Zoo, Museum of Natural History and Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the evening, Coué would have a two-hour interview with a journalist in English, which he learned in an intensive course so that he could lecture in England and America. One reporter asked Lyford what would happen if people decided to show up for the lectures without tickets or tried to visit the Frenchman at his hotel or even Lyford’s house.

Lyford paused, as if he hadn’t thought of this, and left the question unanswered. Policemen then entered the room to escort Coué to a car that was waiting to take him to Lyford’s home in New Jersey where he would spend the rest of the afternoon resting.

As Coué disembarked, he saw the rowdy throngs of people who were there to welcome him.

“I was inexpressibly surprised and touched that I should be considered worthy of such a reception,” Coué later wrote. “Shall I be accused of a lack of modesty if I say that I am proud and gratified to have been greeted thus?”

Writing prompt: What's the best piece of simple, self-help advice you've gotten? Who gave you that advice and how (and when) have you used it in your day-to-day life?

Endnotes

Update on the Seine River: A 75-year-old American man swam in the Seine yesterday amid concerns that the river would not be clean enough for Olympic events. The man, Joel McClure, said: "I may regret having swum, but if I come back alive, it will prove that the French have done a good job cleaning up the river." Spoken like a man who is afraid of a shark attack, not bacteria. Hours after McClure's swim, data showed that the Seine's water quality had improved in the past week, so we'll see if those trends continue.

Just wondering: What are you reading that you're loving right now? Let's get a roundup of good titles – old or new – that we can share with each other and discuss.

Where I hope you'll donate this week: The Ocean Conservancy has dedicated its mission to protecting our oceans from the greatest challenges that face it today. From engaging in important political discussions and changes to working towards a trash-free ocean, the organization is at the forefront of protecting the health and safety of our oceans. Please, if you can, give what you can to support this very important work.

Paige Bowers Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.